All the Kings Horses and All the Kings Men Never Put Us Together Again

| "Humpty Dumpty" | |

|---|---|

Illustration by W. W. Denslow, 1904 | |

| Nursery rhyme | |

| Published | 1797 |

Humpty Dumpty is a graphic symbol in an English language nursery rhyme, probably originally a riddle and one of the best known in the English-speaking world. He is typically portrayed every bit an anthropomorphic egg, though he is not explicitly described equally such. The starting time recorded versions of the rhyme date from late eighteenth-century England and the tune from 1870 in James William Elliott's National Nursery Rhymes and Nursery Songs.[1] Its origins are obscure, and several theories accept been advanced to suggest original meanings.

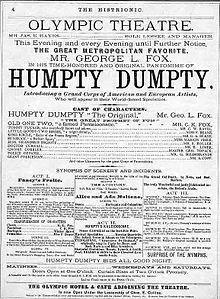

Humpty Dumpty was popularised in the U.s. on Broadway by actor George L. Pull a fast one on in the pantomime musical Humpty Dumpty.[2] The evidence ran from 1868 to 1869, for a total of 483 performances, becoming the longest-running Broadway show until it was surpassed in 1881 by Hazel Kirke.[three] Equally a character and literary allusion, Humpty Dumpty has appeared or been referred to in many works of literature and pop civilization, particularly English author Lewis Carroll'due south 1871 book Through the Looking-Glass, in which he was described equally an egg. The rhyme is listed in the Roud Folk Song Alphabetize as No. 13026.

Lyrics and melody [edit]

The rhyme is one of the best known in the English language language. The common text from 1954 is:[4]

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great autumn.

All the rex'south horses and all the male monarch'due south men

Couldn't put Humpty together again.

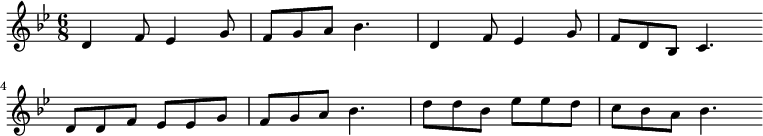

Information technology is a single quatrain with external rhymes[5] that follow the design of AABB and with a trochaic metre, which is common in plant nursery rhymes.[6] The melody normally associated with the rhyme was commencement recorded by composer and nursery rhyme collector James William Elliott in his National Plant nursery Rhymes and Nursery Songs (London, 1870), as outlined beneath:[7]

Origins [edit]

Illustration from Walter Crane's Mother Goose'due south Nursery Rhymes (1877), showing Humpty Dumpty as a boy

The earliest known version was published in Samuel Arnold'southward Juvenile Amusements in 1797[1] with the lyrics:[4]

Humpty Dumpty saturday on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a peachy fall.

Four-score Men and 4-score more,

Could not brand Humpty Dumpty where he was before.

William Carey Richards (1818–1892) quoted the poem in 1843, commenting, "when we were five years sometime ... the following parallel lines... were propounded as a riddle ... Humpty-dumpty, reader, is the Dutch or something else for an egg".[8]

A manuscript add-on to a re-create of Mother Goose's Melody published in 1803 has the mod version with a different last line: "Could non fix Humpty Dumpty upward again".[4] It was published in 1810 in a version of Gammer Gurton's Garland.[nine] (Annotation: Original spelling variations left intact.)

Humpty Dumpty sate on a wall,

Humpti Dumpti had a neat autumn;

Threescore men and threescore more than,

Cannot identify Humpty dumpty as he was before.

In 1842, James Orchard Halliwell published a collected version as:[ten]

Humpty Dumpty lay in a beck.

With all his sinews effectually his neck;

Twoscore Doctors and 40 wrights

Couldn't put Humpty Dumpty to rights!

The modern-twenty-four hour period version of this nursery rhyme, as known throughout the UK since at to the lowest degree the mid-twentieth century, is as follows:

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great autumn;

All the King'southward horses

And all the Male monarch's men,

Couldn't put Humpty together again.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the 17th century the term "humpty dumpty" referred to a drink of brandy boiled with ale.[four] The riddle probably exploited, for misdirection, the fact that "humpty dumpty" was also eighteenth-century reduplicative slang for a brusk and clumsy person.[xi] The riddle may depend upon the supposition that a clumsy person falling off a wall might non be irreparably damaged, whereas an egg would exist. The rhyme is no longer posed equally a riddle, since the answer is at present and so well known. Similar riddles have been recorded by folklorists in other languages, such equally "Boule Boule" in French, "Lille Trille" in Swedish and Norwegian, and "Runtzelken-Puntzelken" or "Humpelken-Pumpelken" in unlike parts of Federal republic of germany—although none is as widely known as Humpty Dumpty is in English.[four] [12]

Meaning [edit]

The rhyme does non explicitly country that the subject is an egg, possibly because information technology may have been originally posed as a riddle.[4] There are also diverse theories of an original "Humpty Dumpty". One, avant-garde past Katherine Elwes Thomas in 1930[thirteen] and adopted by Robert Ripley,[4] posits that Humpty Dumpty is Male monarch Richard Iii of England, depicted every bit humpbacked in Tudor histories and particularly in Shakespeare's play, and who was defeated, despite his armies, at Bosworth Field in 1485. All that is known for certain, is that the line, "all kings horses and all the kings men couldn't put humpty together once more" did not hateful the horses physically assisted humpty. Merely rather, was a metaphor for the crowns resources.

In 1785, Francis Grose'southward Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Natural language noted that a "Humpty Dumpty" was "a short clumsey [sic] person of either sex, also ale boiled with brandy"; no mention was made of the rhyme.[14]

Dial in 1842 suggested jocularly that the rhyme was a metaphor for the downfall of Cardinal Wolsey; but as Wolsey was not buried in his intended tomb, so Humpty Dumpty was not buried in his shell.[15]

Professor David Daube suggested in The Oxford Magazine of sixteen February 1956 that Humpty Dumpty was a "tortoise" siege engine, an armoured frame, used unsuccessfully to approach the walls of the Parliamentary-held urban center of Gloucester in 1643 during the Siege of Gloucester in the English Ceremonious War. This was on the ground of a contemporary business relationship of the attack, but without prove that the rhyme was continued.[16] The theory was part of an bearding series of articles on the origin of nursery rhymes and was widely acclaimed in academia,[17] but it was derided by others every bit "ingenuity for ingenuity'due south sake" and declared to be a spoof.[18] [19] The link was nevertheless popularised by a children's opera All the Male monarch'south Men past Richard Rodney Bennett, commencement performed in 1969.[20] [21]

From 1996, the website of the Colchester tourist lath attributed the origin of the rhyme to a cannon recorded every bit used from the church of St Mary-at-the-Wall by the Royalist defenders in the siege of 1648.[22] In 1648, Colchester was a walled boondocks with a castle and several churches and was protected by the city wall. The story given was that a large cannon, which the website claimed was colloquially called Humpty Dumpty, was strategically placed on the wall. A shot from a Parliamentary cannon succeeded in damaging the wall beneath Humpty Dumpty, which acquired the cannon to tumble to the ground. The Royalists (or Cavaliers, "all the King'south men") attempted to raise Humpty Dumpty on to some other office of the wall, merely the cannon was so heavy that "All the King'due south horses and all the Rex'southward men couldn't put Humpty together once again". Author Albert Jack claimed in his 2008 book Pop Goes the Weasel: The Cloak-and-dagger Meanings of Nursery Rhymes that there were two other verses supporting this claim.[23] Elsewhere, he claimed to take constitute them in an "erstwhile dusty library, [in] an even older book",[24] but did non land what the volume was or where it was found. It has been pointed out that the ii boosted verses are not in the fashion of the seventeenth century or of the existing rhyme, and that they do not fit with the earliest printed versions of the rhyme, which exercise not mention horses and men.[22]

In popular civilization [edit]

Humpty Dumpty has go a highly popular nursery rhyme character. American actor George L. Fox (1825–77) helped to popularise the character in nineteenth-century stage productions of pantomime versions, music, and rhyme.[25] The character is also a mutual literary allusion, particularly to refer to a person in an insecure position, something that would be difficult to reconstruct in one case broken, or a short and fat person.[26]

Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking-Glass [edit]

Humpty Dumpty appears in Lewis Carroll'southward Through the Looking-Glass (1871), a sequel to Alice in Wonderland from six years prior. Alice remarks that Humpty is "exactly like an egg," which Humpty finds to be "very provoking." Alice clarifies that she said he looks similar an egg, not that he is one. They discuss semantics and pragmatics[27] when Humpty Dumpty says, "my proper name means the shape I am," and later:[28]

"I don't know what you mean by 'glory,' " Alice said.

Humpty Dumpty smiled contemptuously. "Of course yous don't—till I tell you. I meant 'there's a nice knock-down argument for you lot!'"

"But 'glory' doesn't hateful 'a nice knock-down argument'," Alice objected.

"When I use a give-and-take," Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, "information technology means simply what I choose information technology to mean—neither more nor less."

"The question is," said Alice, "whether y'all tin can make words mean so many different things."

"The question is," said Humpty Dumpty, "which is to be chief—that's all."

Alice was too much puzzled to say anything, so subsequently a infinitesimal Humpty Dumpty began again:

"They've a temper, some of them—particularly verbs, they're the proudest—adjectives you can do anything with, just not verbs—however, I tin can manage the whole lot! Impenetrability! That'south what I say!"

This passage was used in United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland past Lord Atkin in his dissenting judgement in the seminal instance Liversidge v. Anderson (1942), where he protested about the distortion of a statute by the majority of the House of Lords.[29] It as well became a popular citation in United States legal opinions, actualization in 250 judicial decisions in the Westlaw database as of 19 April 2008[update], including ii Supreme Court cases (TVA v. Hill and Zschernig v. Miller).[xxx]

A. J. Larner suggested that Carroll'southward Humpty Dumpty had prosopagnosia on the basis of his clarification of his finding faces hard to recognise:[31]

"The face is what one goes by, mostly," Alice remarked in a thoughtful tone. "That's just what I complain of," said Humpty Dumpty. "Your confront is the same equally everybody has—the two eyes,—" (marker their places in the air with his pollex) "nose in the eye, mouth under. It'due south ever the aforementioned. Now if you had the 2 eyes on the same side of the nose, for instance—or the rima oris at the acme—that would be some aid."

James Joyce'due south Finnegans Wake [edit]

James Joyce used the story of Humpty Dumpty as a recurring motif of the Autumn of Human being in the 1939 novel Finnegans Wake.[32] [33] One of the about easily recognizable references is at the terminate of the 2nd affiliate, in the first poetry of the Ballad of Persse O'Reilly:

Have yous heard of 1 Humpty Dumpty

How he fell with a roll and a rumble

And curled up similar Lord Olofa Crumple

Past the butt of the Magazine Wall,

(Chorus) Of the Magazine Wall,

Hump, helmet and all?

In film, literature and music [edit]

Robert Penn Warren'south 1946 American novel All the Rex'south Men is the story of populist pol Willie Stark's rise to the position of governor and eventual fall, based on the career of the infamous Louisiana Senator and Governor Huey Long. It won the 1947 Pulitzer Prize and was twice made into a moving picture in 1949 and 2006, the former winning the Academy Award for best motion picture.[34] This was echoed in Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward's book All the President's Men, about the Watergate scandal, referring to the failure of the President's staff to repair the damage once the scandal had leaked out. Information technology was filmed as All the President's Men in 1976, starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman.[35]

In 1983, an advertising for Kinder Surprise featuring a realistic version of the Humpty Dumpty graphic symbol (designed by Mike Quinn, who worked at the Jim Henson'southward Brute Shop) and directed by Mike Portelly, was banned shortly after release, due to beingness highly unsettling. The advertizement aired only on ITV and its franchises.

In 2021, American band AJR released a song, titled Humpty Dumpty, for their album, OK Orchestra. The song uses the nursery rhyme equally a parallel for hiding i'south true emotions as things, typically unpleasant, happen to the vocalist.

Jasper Fforde's 2005 British novel The Big Over Easy ISBN 978-0-340-89710-2 is an exercise in absurdity, in which Humpty Stuyvesant Van Dumpty III has been murdered, and Detective Jack Spratt of the Plant nursery Law-breaking Partition is set the task of solving the mystery.

In science [edit]

Humpty Dumpty has been used to demonstrate the second law of thermodynamics. The law describes a procedure known every bit entropy, a measure of the number of specific ways in which a system may exist arranged, frequently taken to be a measure of "disorder". The higher the entropy, the higher the disorder. After his fall and subsequent shattering, the inability to put him together again is representative of this principle, as it would be highly unlikely (though non incommunicable) to return him to his before land of lower entropy, as the entropy of an isolated system never decreases.[36] [37] [38]

Come across also [edit]

- List of nursery rhymes

References [edit]

- ^ a b Emily Upton (24 April 2013). "The Origin of Humpty Dumpty". What I Learned Today. Retrieved nineteen September 2015.

- ^ Kenrick, John (2017). Musical Theatre: A History. ISBN9781474267021 . Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ Humpty Dumpty at the Internet Broadway Database

- ^ a b c d e f g Opie & Opie (1997), pp. 213–215.

- ^ J. Smith, Poetry Writing (Teacher Created Resources, 2002), ISBN 0-7439-3273-0, p. 95.

- ^ P. Hunt, ed., International Companion Encyclopedia of Children's Literature (London: Routledge, 2004), ISBN 0-203-16812-7, p. 174.

- ^ J. J. Fuld, The Book of Earth-Famous Music: Classical, Popular, and Folk (Courier Dover Publications, 5th ed., 2000), ISBN 0-486-41475-2, p. 502.

- ^ Richards, William Carey (March–April 1844). "Monthly chat with readers and correspondents". The Orion. Penfield, Georgia. Two (5 & 6): 371.

- ^ Joseph Ritson, Gammer Gurton'due south Garland: or, the Nursery Parnassus; a Pick Collection of Pretty Songs and Verses, for the Amusement of All Fiddling Good Children Who Can Neither Read Nor Run (London: Harding and Wright, 1810), p. 36.

- ^ J. O. Halliwell-Phillipps, The Plant nursery Rhymes of England (John Russell Smith, 6th ed., 1870), p. 122.

- ^ Due east. Partridge and P. Beale, Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English language (Routledge, eighth ed., 2002), ISBN 0-415-29189-5, p. 582.

- ^ Lina Eckenstein (1906). Comparative Studies in Nursery Rhymes. pp. 106–107. OL 7164972M. Retrieved xxx Jan 2018 – via archive.org.

- ^ E. Commins, Lessons from Mother Goose (Lack Worth, Fl: Humanics, 1988), ISBN 0-89334-110-10, p. 23.

- ^ Grose, Francis (1785). A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue. S. Hooper. pp. xc–.

- ^ "Juvenile Biography No Iv: Humpty Dumpty". Punch. 3: 202. July–December 1842.

- ^ "Nursery Rhymes and History", The Oxford Magazine, vol. 74 (1956), pp. 230–232, 272–274 and 310–312; reprinted in: Calum One thousand. Carmichael, ed., Collected Works of David Daube, vol. 4, "Ideals and Other Writings" (Berkeley, CA: Robbins Drove, 2009), ISBN 978-one-882239-15-3, pp. 365–366.

- ^ Alan Rodger. "Obituary: Professor David Daube". The Independent, 5 March 1999.

- ^ I. Opie, 'Playground rhymes and the oral tradition', in P. Hunt, South. G. Bannister Ray, International Companion Encyclopedia of Children's Literature (London: Routledge, 2004), ISBN 0-203-16812-vii, p. 76.

- ^ Iona and Peter Opie, ed. (1997) [1951]. The Oxford Lexicon of Plant nursery Rhymes (2d ed.). Oxford: Oxford Academy Press. p. 254. ISBN978-0-xix-860088-six.

- ^ C. M. Carmichael (2004). Ideas and the Man: remembering David Daube. Studien zur europäischen Rechtsgeschichte. Vol. 177. Frankfurt: Vittorio Klostermann. pp. 103–104. ISBNthree-465-03363-ix.

- ^ "Sir Richard Rodney Bennett: All the King'south Men". Universal Edition. Retrieved eighteen September 2012.

- ^ a b "Putting the 'dump' in Humpty Dumpty". The BS Historian. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ^ A. Jack, Pop Goes the Weasel: The Underground Meanings of Nursery Rhymes (London: Allen Lane, 2008), ISBN 1-84614-144-3.

- ^ "The Real Story of Humpty Dumpty, by Albert Jack". Archived 27 February 2010 at the Wayback Auto, Penguin.com (USA). Retrieved 24 Feb 2010.

- ^ L. Senelick, The Historic period and Stage of George L. Fox 1825–1877 (University of Iowa Press, 1999), ISBN 0877456844.

- ^ E. Webber and M. Feinsilber, Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of Allusions (Merriam-Webster, 1999), ISBN 0-87779-628-9, pp. 277–viii.

- ^ F. R. Palmer, Semantics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, second edn., 1981), ISBN 0-521-28376-0, p. 8.

- ^ L. Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass (Raleigh, Due north Carolina: Hayes Barton Press, 1872), ISBN 1-59377-216-five, p. 72.

- ^ K. Lewis (1999). Lord Atkin. London: Butterworths. p. 138. ISBNone-84113-057-5.

- ^ Martin H. Redish and Matthew B. Arnould, "Judicial review, constitutional interpretation: proposing a 'Controlled Activism' alternative", Florida Law Review, vol. 64 (6), (2012), p. 1513.

- ^ A. J. Larner (1998). "Lewis Carroll's Humpty Dumpty: an early on report of prosopagnosia?". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 75 (7): 1063. doi:x.1136/jnnp.2003.027599. PMC1739130. PMID 15201376.

- ^ J. S. Atherton, The Books at the Wake: A Report of Literary Allusions in James Joyce's Finnegans Wake (1959, SIU Press, 2009), ISBN 0-8093-2933-6, p. 126.

- ^ Worthington, Mabel (1957). "Nursery Rhymes in Finnegans Wake". The Journal of American Folklore. 70 (275): 37–48.

- ^ G. Fifty. Cronin and B. Siegel, eds, Conversations With Robert Penn Warren (Jackson, MS: University Printing of Mississippi, 2005), ISBN i-57806-734-0, p. 84.

- ^ M. Feeney, Nixon at the Movies: a Book About Conventionalities (Chicago IL: Academy of Chicago Press, 2004), ISBN 0-226-23968-iii, p. 256.

- ^ Chang Kenneth (thirty July 2002). "Humpty Dumpty Restored: When Disorder Lurches Into Lodge". The New York Times . Retrieved two May 2013.

- ^ Lee Langston. "Part 3 – The Second Police of Thermodynamics" (PDF). Hartford Courant. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ W.South. Franklin (March 1910). "The 2d Law Of Thermodynamics: Its Basis In Intuition And Common Sense". The Pop Science Monthly: 240.

External links [edit]

- Humpty-Dumpty themed educational activity

- Humpty-Dumpty themed educational and craft pages

- Library of Congress' Facsimile of the 1899 illustrated edition of Through the Looking-Glass

- Loyal Books: Mother Goose in Prose by L. Frank Baum

- Loyal Books: Through the Looking Glass by Lewis Carroll

- The Carol of Persse O'Reilly

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humpty_Dumpty

0 Response to "All the Kings Horses and All the Kings Men Never Put Us Together Again"

Post a Comment